Download the Full Report

On January 15, 2021, the UK Supreme Court issued its widely anticipated decision in the Financial Conduct Authority’s business interruption (BI) test case. Learn about the reinsurance implications of the case from Guy Carpenter’s experts.

On January 15, 2021, the UK Supreme Court issued its widely anticipated decision in the Financial Conduct Authority’s business interruption (BI) test case. The FCA brought the test case to resolve uncertainty for certain BI policyholders affected by the COVID pandemic. Although the Court ruled that some forms of BI insurance cover COVID losses, the Court adopted a narrow definition of a COVID “occurrence” — an illness suffered by just one person or arguably several people in one household — that has raised questions about the meaning of the word “occurrence” in other contexts.

Some commentators have suggested that the definition of “occurrence” in the test case could also apply in the reinsurance context — specifically in the context of “Loss Occurrence” clauses (also called “aggregation provisions”) in catastrophic excess of loss treaties (“Cat XL”). In reinsurance, aggregation is the pooling of multiple losses into a single loss occurrence. How losses are aggregated will affect both a cedent’s retention and indemnity limits.

Because the test case addressed fundamentally different coverage questions, its findings do not govern the reinsurance response to COVID losses. Below, we highlight textual arguments in the UK Supreme Court’s decision to demonstrate that invoking the test case outside of its primary insurance context would be inconsistent with the Court’s own reasoning — and inconsistent with the custom and practice of the reinsurance industry.

The Court’s Narrow Construction of “Occurrence”

The key policy language addressed by the UK Supreme Court included the following (or similar) words: “We shall indemnify you in respect of interruption. . . with the Business in consequence of / arising from . . .any. . . occurrence of a Notifiable Disease within a radius of 25 miles of the Premises.” This type of so-called disease clause provides insurance coverage for business interruption caused by disease.

The Court rejected the FCA’s contention that an “occurrence” under a disease clause included a nationwide outbreak of COVID. The Court ruled that the word “occurrence” as used here does not refer to an outbreak of any kind. Instead, the Court held that “each case of illness sustained by an individual [is] a separate occurrence.”

In a critical paragraph, the Court explained that an outbreak of COVID cannot be an insurance “occurrence”:

A disease that spreads is not something that occurs at a particular time and place and in a particular way: it occurs at a multiplicity of different times and places and may occur in different ways involving differing symptoms of greater or less severity. Nor for that matter could an “outbreak” of disease be regarded as one occurrence . . . Still less could it be said that all the cases of COVID-19 in England (or in the United Kingdom or throughout the world) which had arisen by any given date in March 2020 constituted one occurrence. On any reasonable or realistic view, those cases comprised thousands of separate occurrences of COVID-19.

The Supreme Court agreed with the High Court’s reasoning that the “insured peril” is COVID whenever and wherever it occurs, and the peril is not limited to any particular occurrence or outbreak.

Must the Reinsurance “Event” Be Narrow As Well?

Many CAT XL treaties have Loss Occurrence definitions that allow for the aggregation of losses arising from “one event.” The following language is typical: “Loss Occurrence means the sum of all individual losses directly occasioned by any one disaster, accident or loss or series of disasters, accidents or losses arising out of one event.”

Based on the UK Supreme Court’s reasoning in the test case (especially the paragraph quoted above), it has been suggested that the “one event” for purposes of aggregating COVID losses cannot be the outbreak of COVID itself.

Context is Everything

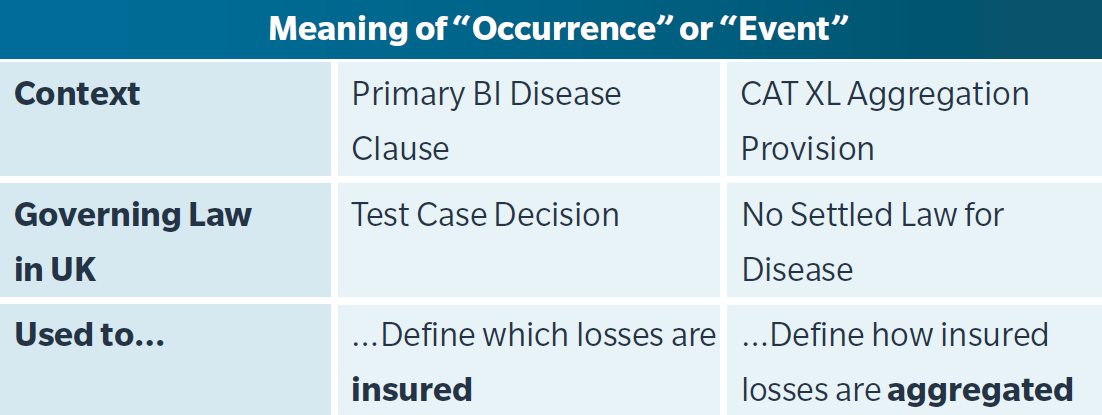

The Court’s decision does not apply to the meaning of “occurrence” or “event” in the Loss Occurrence provisions of a CAT XL reinsurance contract. The Court itself stated that its narrow definition of “occurrence” was based on the context before it, namely the “interpretation which makes best sense of the [disease] clause” in the primary policies under review.

Thus, the Court was deciding whether insurers were liable under a primary BI disease extension—nothing more.

In a CAT XL contract, the question of which insured losses are reinsured is settled. The typical “Business Covered” section of a CAT XL establishes that it covers all property business and thus all BI losses (including non-damage BI extensions). In the CAT XL context, the term “event” does not limit the scope of the insured peril, but rather the extent to which insured losses may be aggregated for retention and limit purposes. The following chart summarizes this critical distinction:

In contract interpretation, context is everything. As the Court said, an inquiry into the meaning of the word “event” is not a question to which a general answer can be given. It always depends on the context in which the question is asked.

The test case does not interpret words or terms in the context of a reinsurance contract. On the contrary, the Court was interpreting a primary property BI policy and was clearly influenced by numerous features of such a policy. But the features of a primary property BI policy do not exist in a reinsurance contract, which is why the interpretation of a primary policy cannot determine the meaning of “event” in a reinsurance aggregation provision. For example:

- The “occurrence” in a disease clause is defined as a disease occurring within a 25-mile radius of the single insured premises. The Court explained that it is only cases of illness within the radius specified in the clause that are covered.

- All of the other sub-clauses of the BI extensions refer to narrow “occurrences” “at the premises” — for example, the discovery of vermin or pests, defects in drains or a murder on site. The Court reasoned that these “occurrences” take place “at a particular time and place,” and thus disease clauses should be read in the same way.

- The BI policies reviewed included an “Indemnity Period” that runs from “the date of the occurrence.” The Court reasoned that “[i]t is implicit in this definition that an ‘occurrence’ is something that happens on a particular date and not something capable of extending over more than one date.”

- The definition of “Notifiable Disease” in the BI policies considered by the Court is an “illness sustained by any person” from a disease “an outbreak of which” requires notifying a government authority. Thus, the policy explicitly states that an “occurrence” is an infection in “any person” — i.e., one person — and is separate from a widespread outbreak of a disease.

None of these contextual limits exist in the aggregation provision of a CAT XL reinsurance contract. A CAT XL contract has no parallel clauses with extremely narrow “events” like the discovery of vermin, drainage problems or homicide at a single location.

Likewise, the existence of an hours clause demonstrates that a reinsurance Loss Occurrence can extend for weeks. Cedents have the freedom to choose when the relevant Loss Occurrence starts, unlike in primary property BI policies, and contrary to the Court’s description of the trigger of a primary policy disease clause, which has a fixed starting point. A CAT XL does not limit an “event” in the way the definition of “Notifiable Disease” limits an “occurrence” in a disease clause.

In contrast to the BI policies at issue in the test case, a CAT XL contract uses the term “event” in a context that warrants a broad interpretation. Per the common definition of Loss Occurrence, an “event” is broad enough to include losses occasioned by a “series of disasters.” Additionally, an “event” is broad enough to include the extent of disasters typically referenced in a CAT XL—for example, hurricanes and wildfires—events that are often widespread, of substantial duration and multi-jurisdictional.

Finally, most reinsurance contracts require the resolution of disputes by arbitration. And arbitration provisions often direct arbitrators to (1) treat the contract as “an honorable engagement rather than as merely a legal obligation” and (2) base decisions on the “custom and practice” of the reinsurance business. These provisions require arbitrators to consider the context of the reinsurance business. As such, they ought to prevent a mechanical application of the test case decision to CAT XL contracts. An honorable engagement between cedent and reinsurer—or an engagement that is consistent with the custom and practice of the reinsurance business—should acknowledge the stark contrast between the context of a Loss Occurrence clause in a CAT XL treaty and an “occurrence” of COVID in a primary policy’s disease clause.

Conclusion

Though not binding outside the United Kingdom, the Court’s analysis of an “occurrence”—especially its ruling that a COVID outbreak cannot be an occurrence in certain primary BI extensions—has the potential to confuse the conversation around reinsurance responses to COVID losses. The clarifying response is simple: context is everything. The context and analysis of the test case decision demonstrate that it cannot answer reinsurance aggregation questions. To apply the Court’s reasoning to reinsurance would risk defeating the very intent and purpose of CAT XL contracts, defy industry customs and expectations, and distort the language used in aggregation provisions.